Global Travel Information

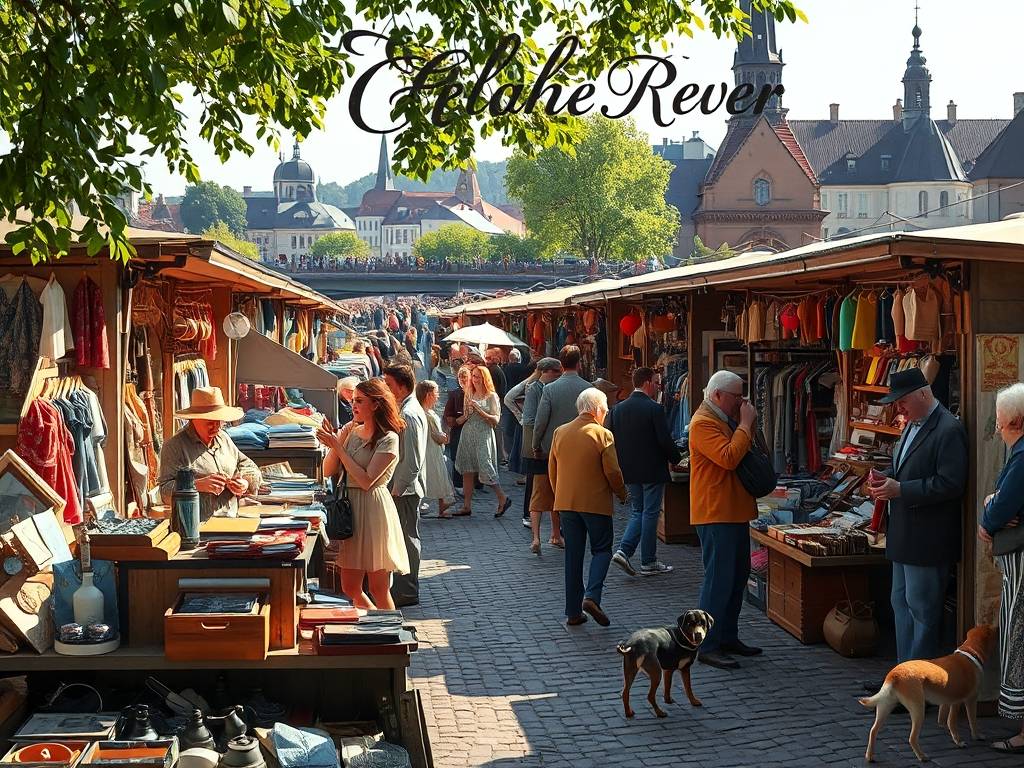

Elbe River Antique Markets: Hunt for Vintage Treasures

A Stroll Through Time: Unearthing History Along the Elbe's Antique Markets

The Elbe River, a silvery ribbon weaving through the heart of Europe, has for centuries been a conduit of commerce, culture, and conflict. Its waters have carried Saxon kings and Swedish armies, Romantic poets and Communist officials. But on certain weekends, along its grassy banks and in the cobbled squares of its historic towns, the river transforms into a stage for a different kind of exchange. Here, the flow is not of water, but of time itself, as the Elbe's famed antique markets spring to life. This is not merely shopping; it is a pilgrimage for the curious, a treasure hunt for those who believe objects have souls and stories to tell.

The allure of these markets lies not in the pristine, clinically lit galleries of high-end auction houses, but in their beautiful, beguiling chaos. The air is thick with the scent of aged wood, old leather, and faint hints of polish. Sunlight glints off tarnished silver, dances through the vibrant hues of hand-painted porcelain, and catches the dust motes dancing above stacks of yellowed books. Each stall is a miniature museum, a curated collection of a bygone era, waiting for a new custodian. The hunt is as much about the discovery as it is about the object. It requires a keen eye, a patient hand, and a willingness to engage in the gentle, rhythmic dance of negotiation.

To understand the treasure, one must first understand the ground from which it springs. The stretch of the Elbe flowing through Saxony, particularly around its crown jewel, Dresden, is uniquely fertile territory for such markets. Dresden, the "Florence on the Elbe," was a centre of unparalleled artistic and artisanal excellence for centuries. The workshops of Meissen produced porcelain that was the envy of the world. The forests of the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains) gave rise to a tradition of intricate woodworking and toy-making. Silver smiths, glassblowers, and instrument makers all flourished under the patronage of the Saxon electors.

Then came the cataclysm of February 13, 1945. The firestorm that engulfed Dresden did not just destroy buildings; it vaporised lifetimes of creation. In the decades of Communist rule that followed in East Germany, many of these traditions were collectivised, their quality often diminished, while pre-war possessions became hidden away, sometimes out of necessity, sometimes as quiet acts of preserving a past the state sought to overwrite. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 unlocked this hidden history. Attics were emptied, barns cleared out, and family legacies, once concealed, were brought into the light. The antique markets along the Elbe became, and remain, the primary clearing house for this vast, rediscovered material culture. Every piece carries the invisible weight of this history—of brilliance, destruction, silence, and resurrection.

A typical hunt might begin at the largest and most famous of these markets, the Dresdner Antik- und Trödelmarkt on the banks of the Elbe, near the Albertinum museum. Here, under the gaze of the city's meticulously rebuilt Baroque skyline, hundreds of vendors lay out their wares on blankets and folding tables. The variety is staggering. One can find everything from exquisite Meissen figurines—a shepherdess with a meticulously painted face, a prancing horse—to more humble, yet equally fascinating, GDR-era (East German) household items. A collection of vintage camera lenses might lie next to a stack of porcelain coffee cups bearing the insignia of an Interhotel chain. For the collector of militaria, there are Iron Crosses and Soviet badges; for the bibliophile, leather-bound volumes of Goethe sit beside dog-eared propaganda pamphlets from the 1950s. The key is to look closely. That small, tarnished silver spoon might bear the mark of a renowned Dresden silversmith; that chipped vase might be an early 20th-century piece from the VEB Meissen factory.

But the true connoisseur knows that the greatest treasures are often found away from the main tourist thoroughfares. A short drive up the Elbe leads to the charming town of Meissen itself, home to the iconic castle and cathedral perched high above the river. The antique market here is smaller, more intimate, and unsurprisingly, has a profound focus on porcelain. While the Albrechtsburg castle produces its world-famous wares, the market below offers fragments of its history. One might find a plate with a hairline crack, a cup missing its saucer, or a figurine with a restored hand. These "imperfect" pieces are often more affordable and, in their way, more authentic. They are survivors. They have been used, loved, broken, and preserved. A vendor, often with the thoughtful demeanor of a scholar, might explain the nuances of a blue onion pattern versus a red dragon, or how to identify a genuine 18th-century mark from a later reproduction.

Further upstream, the landscape grows more dramatic, with sandstone cliffs rising steeply from the river. In towns like Pirna and Königstein, the markets have a more rustic, regional flavour. Here, the treasures of the Erzgeburgian woodworkers take centre stage. Delicately carved Christmas pyramids, nutcrackers with stern, painted faces, and Räuchermännchen (incense smokers) in the form of miners, foresters, and townsfolk are laid out with care. These are not mere decorations; they are artifacts of a deep-rooted folk culture, each whorl of wood carved by hand, each face telling a story of life in the mountains. One might also stumble upon antique linens, beautifully embroidered by generations of Saxon women, or rustic furniture bearing the patina of a hundred years of use.

The hunt itself is a ritual. It begins with a slow, sweeping gaze, allowing the eye to be caught not by the obvious, but by the unusual—a unique shape, a peculiar colour, a glint of something promising beneath a layer of grime. Then comes the touch. Picking up an object is crucial. One feels the weight of a porcelain cup, testing its substance. The fingers trace the smoothness of a polished stone, the roughness of a carved wooden surface, the coolness of aged metal. This tactile connection is the first step in hearing the object's story.

The next, and perhaps most vital, part of the ritual is the conversation with the vendor. These are not mere salespeople; they are curators, historians, and storytellers. A simple question—"What can you tell me about this?"—can unlock a fascinating narrative. An elderly vendor might recall how he acquired a particular piece of Art Deco jewellery from an estate in Leipzig. Another might explain the historical context of a collection of pre-war postcards depicting a Dresden that no longer exists. This human interaction, this exchange of knowledge, is what separates the antique market from the impersonal transaction of online shopping. It adds a layer of provenance and personality to the purchase.

Successfully navigating the final hurdle—the negotiation—requires respect and a subtle touch. Haggling is expected, but it is a dance, not a battle. It begins with a show of genuine interest, followed by a respectful question about the possibility of a better price. The goal is a fair price that acknowledges the value of the item and the knowledge of the seller, while also fitting the budget of the hunter. The satisfaction of reaching an agreement is a reward in itself, a shared moment of understanding between two people connected by a shared appreciation for a piece of the past.

Ultimately, a day spent hunting for vintage treasures along the Elbe is a journey through layers of European history. It is a tangible connection to the artisans of the Baroque age, the families who lived through war and peace, and the quiet resilience of traditions that refused to die. The object you carry away—be it a delicate piece of porcelain, a sturdy wooden toy, or a simple, well-worn tool—is more than a souvenir. It is a fragment of a story, a vessel of memory, waiting to begin a new chapter in a new home. It is a silent promise that beauty and craftsmanship, no matter how buried by time or tragedy, can always be rediscovered, if one only knows where to look. And on the banks of the timeless Elbe, the looking is its own profound reward.

相关文章

- Elbe River Tubing Trips: Relax & Float Along

- Elbe River Fishing Charters: Hire a Guide for the Day

- Elbe River Bird Watching Tours: Spot Rare Species

- Elbe River Wildlife Safaris: Explore Nature Near the River

- Elbe River Botanical Tours: See Rare Plants & Flowers

- Elbe River Archaeological Tours: Discover Ancient Sites

- Elbe River Historical Walking Tours: Explore On Foot

- Elbe River Cycling Tours: Bike Along Scenic Paths

- Elbe River Driving Tours: Road Trips Near the Waterway

- Elbe River Train Tours: Relax & Enjoy the Views

发表评论

评论列表

- 这篇文章还没有收到评论,赶紧来抢沙发吧~